Deficient Lmna in fibroblasts: an emerging role of non-cardiomyocytes in DCM

LMNA gene encodes intermediate filament proteins Lamin A/C. Lamin A and Lamin C polymerize to form nuclear lamina, mainly located in the inner layer of the nuclear envelope. As an essential component of the nuclear envelope, Lamins are necessary for nuclear structural integrity and participate in chromatin organization, cell cycle regulation, and DNA damage response[1]. By far, LMNA has the largest and most diverse number of disease-related mutations in the human genome[2]. More than 450 different mutations are linked to laminopathies among organs and tissues, including peripheral nerve (Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy), adipose tissue (familial lipodystrophy), muscle tissue (muscular dystrophy, dilated cardiomyopathy, and arrhythmia), multiple systems with accelerating aging (Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome)[3]. Most LMNA mutations affect the striated muscles; about 165 LMNA mutations have been associated with dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM)[4].

DCM is one of the most common causes of heart failure and sudden cardiac death in the aging population, characterized by ventricular dilation and systolic dysfunction. Notably, gene mutation contributes to approximately 40% of DCM causations, and more than 60 genes, including LMNA, have been identified as relevant to DCM. LMNA mutations lead to 5%-10% of DCM cases, with an age-related penetrance typically between 30 and 40[5]. 86% of LMNA mutation carriers exhibit cardiac phenotypes over 40, while 7% of the patients are younger than 20[4]. LMNA-related DCM usually presents conduction defect and ventricular arrhythmia, with or without progression into left ventricular enlargement[6]. However, how LMNA mutations are linked to the DCM phenotype remains unclear.

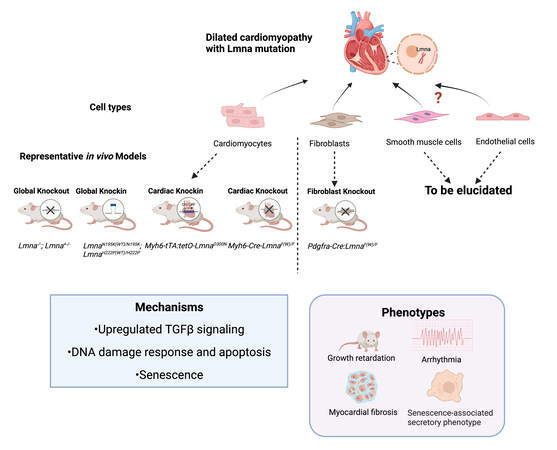

Several murine models have been created to unravel the pathogenic signaling pathways that connect the genotype to phenotype [Figure 1]. Growth retardation, cardiac arrhythmias, increased heart fibrosis, early disease onset, and even premature death are shared among Lamin A/C null (Lmna-/-) mice, mice carrying Lmna point mutations (LmnaN195K/N195K mice, cardiac-specific mutation Myh6-tTA:tetO-LmnaD300N mice), and cardiac-specific knockout mice (Myh6-Cre:LmnaF/F mice)[7-9]. Interestingly, heterozygous lines with listed mutations grow normally at an early stage but progressively develop DCM at about 12 months. Another systemic mutation-introduced mouse line, LmnaH222p/H222P, exhibited DCM in adulthood, while heterozygous mice lived comparably to wild-type mice[10]. Transcriptomic analyses have provided clues to illustrate the pathogenic mechanisms. Abnormal activation of MAPK signaling (ERK1/2, JNK, and p38α) and AKT/mTOR signaling has been found in LmnaH222P/H222P mice, related to the intolerance to energy deficits and decompensation[10]. Upregulation of TGF-β signaling in the LmnaH222P/H222P mouse heart accounts for the myocardial fibrosis. Genes involved in apoptosis, pro-inflammatory cytokines, DNA damage response, and senescence were upregulated upon the Lmna variant-driven activation of TP53 in Myh6-tTA:tetO-LmnaD300N mice[9]. In LmnaN195K/N195K mice, remodeled connexin expression 40/43 on the lateral surface of cardiomyocytes may impair the gap junction communications, while decreased expression of Hf1b/Sp4 in ventricles may affect the cardiac conduction system[8].

Figure 1. Patient-related LMNA mutant mouse models. Most animal models are generated based on Lmna mutation or deletion in cardiomyocytes and have contributed to investigations on DCM pathogenesis. The current fibroblast-specific Lmna-deficient mice demonstrated a similar DCM phenotype compared to cardiomyocyte Lmna-deficient models, with the signature of growth retardation, arrhythmia, and myocardial fibrosis, and senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Mechanistic studies showed upregulation of TGFβ signaling, activation of DNA damage response and apoptosis, and cell senescence. Collectively, cardiac fibroblasts with Lmna deficiency jointly contribute to DCM with cardiomyocytes. With this discovery, the non-cardiomyocytes are emerging as important new players in the pathogenesis of LMNA-DCM. (Created with BioRender.com).

In addition to in vivo models, patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs) have been developed as a new and popular model to mimic human diseases and provide the possibility of precision medicine. Patient-derived hiPSC-CMs carrying LMNA mutations, especially frameshift mutation, are superior models replicating different DCM-related arrhythmia phenotypes and give the opportunities to elucidate the Lamin regulated-calcium handlings mechanism. A patient-derived hiPSC-CMs carrying LMNAS143P, a prevalent mutation in Finland, have shown increased arrhythmia on β-adrenergic stimulation and are more sensitive to hypoxia[11]. Another patient-derived hiPSC-CMs with a frameshift mutation, K117fs, exhibit induced arrhythmias, dysregulation of CAMK2/RYR2 mediated-calcium homeostasis, and electrical abnormalities, consistent with the phenotypes in DCM patients[12]. The aberrant activation of platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) receptor-β (PDGFRB) due to haploinsufficiency of Lamin A/C is considered to contribute to the arrhythmic phenotype in mutant hiPSC-CMs[12].

To date, almost all mechanistic studies on LMNA-related DCM have focused on cardiomyocytes, as cardiomyopathy is considered the disease of cardiomyocytes. However, as mentioned at the beginning, LMNA is widely expressed. The gene carrying the casual mutations in CMs is also expressed in other cell lineages, such as fibroblasts. Emerging evidence indicated that cardiac fibroblasts and fibrosis play a significant role in DCM pathogenesis. However, a knowledge gap remains on whether cardiac fibroblasts also participate in the occurrence of LMNA-associated DCM.

Here, Dr. Marian and his team generated a fibroblast-specific Lmna knockout mouse line and demonstrated that the deletion of Lmna in cardiac fibroblasts contributes to senescence-related DCM phenotype[13]. Lmna in fibroblasts was deleted by crossing PDGF receptor-α recombinase (Pdgfra-Cre) and floxed Lmna

In this paper, the authors elaborately defined the progressive DCM phenotype, thoroughly demonstrating the potential role of fibroblasts in LMNA-DCM, and proposed underlining mechanisms. These findings are remarkable as presenting the first direct evidence that fibroblasts participate in the LMNA-regulated DCM pathogenesis. The study provides a new angle on delineating the underlying mechanism for DCM with LMNA mutations. That is, non-cardiomyocytes such as cardiac fibroblasts, and cardiomyocytes, jointly contribute to DCM pathogenesis. This research and future investigations on the function of LMNA in endothelial and smooth muscle cells will further critical new information for clinical treatments.

A few limitations of the study are noted. As the authors mentioned in the discussion, Pdgfra is not a unique marker for cardiac fibroblasts. The Pdgfra promoter-driven Cre expression may lead to partial deletion of LMNA in other cell types and tissues, eventually affecting the net phenotype. To exclude the effect of non-cardiac-fibroblast LMNA deletion, the authors screened the comprehensive metabolic panel, which suggested no apparent abnormalities in liver or kidney, and electrolyte disturbances, except a reduced glucose level in plasma. Interestingly, around 25% of cardiomyocytes showed LMNA deletion in

In summary, the current study filled the knowledge deficiency of cardiac fibroblasts in developing LMNA deficiency-induced cardiomyopathy. The new information expands the understanding of the pathogenesis of the LMNA-induced DCM.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributionsConceptualization and writing: Wang X, Luo W, Chang J

Creating the graphical abstract and writing: Wang X, Luo W

Supervision: Chang J

Availability of data and materialsNot applicable.

Financial support and sponsorshipThis work was supported by DOD PRMRP Discovery Award PR192609 (Weijia Luo) and American Heart Association-TPA 19TPA34880011, NHLBIR01HL141215, NHLBI R01HL150124, NHLBI R01HL148133 and NHLBI R21HL157708 (Jiang Chang).

Conflicts of interestAll authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participateNot applicable.

Consent for publicationNot applicable.

Copyright© The Author(s) 2022.

REFERENCES

1. Dechat T, Adam SA, Taimen P, Shimi T, Goldman RD. Nuclear lamins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2010;2:a000547.

2. Burke B, Stewart CL. The nuclear lamins: flexibility in function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2013;14:13-24.

3. Charron P, Arbustini E, Bonne G. What should the cardiologist know about lamin disease? Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev 2012;1:22-8.

4. Tesson F, Saj M, Uvaize MM, Nicolas H, Płoski R, Bilińska Z. Lamin A/C mutations in dilated cardiomyopathy. Cardiol J 2014;21:331-42.

5. Hershberger RE, Hedges DJ, Morales A. Dilated cardiomyopathy: the complexity of a diverse genetic architecture. Nat Rev Cardiol 2013;10:531-47.

6. Brodt C, Siegfried JD, Hofmeyer M, et al. Temporal relationship of conduction system disease and ventricular dysfunction in LMNA cardiomyopathy. J Card Fail 2013;19:233-9.

7. Kubben N, Voncken JW, Konings G, et al. Post-natal myogenic and adipogenic developmental: defects and metabolic impairment upon loss of A-type lamins. Nucleus 2011;2:195-207.

8. Mounkes LC, Kozlov SV, Rottman JN, Stewart CL. Expression of an LMNA-N195K variant of A-type lamins results in cardiac conduction defects and death in mice. Hum Mol Genet 2005;14:2167-80.

9. Chen SN, Lombardi R, Karmouch J, et al. DNA Damage response/TP53 pathway is activated and contributes to the pathogenesis of dilated cardiomyopathy associated with LMNA (Lamin A/C) mutations. Circ Res 2019;124:856-73.

10. Arimura T, Helbling-Leclerc A, Massart C, et al. Mouse model carrying H222P-Lmna mutation develops muscular dystrophy and dilated cardiomyopathy similar to human striated muscle laminopathies. Hum Mol Genet 2005;14:155-69.

11. Shah D, Virtanen L, Prajapati C, et al. Modeling of LMNA-related dilated cardiomyopathy using human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cells 2019;8:594.

12. Lee J, Termglinchan V, Diecke S, et al. Activation of PDGF pathway links LMNA mutation to dilated cardiomyopathy. Nature 2019;572:335-40.

13. Rouhi L, Auguste G, Zhou Q, et al. Deletion of the Lmna gene in fibroblasts causes senescence-associated dilated cardiomyopathy by activating the double-stranded DNA damage response and induction of senescence-associated secretory phenotype. J Cardiovasc Aging 2022;2:14.

14. Nicin L, Wagner JUG, Luxán G, Dimmeler S. Fibroblast-mediated intercellular crosstalk in the healthy and diseased heart. FEBS Lett 2022;596:638-54.

15. Acharya A, Baek ST, Banfi S, Eskiocak B, Tallquist MD. Efficient inducible Cre-mediated recombination in Tcf21 cell lineages in the heart and kidney. Genesis 2011;49:870-7.

16. Kanisicak O, Khalil H, Ivey MJ, et al. Genetic lineage tracing defines myofibroblast origin and function in the injured heart. Nat Commun 2016;7:12260.

Cite This Article

Export citation file: BibTeX | RIS

OAE Style

Wang X, Luo W, Chang J. Deficient Lmna in fibroblasts: an emerging role of non-cardiomyocytes in DCM. J Cardiovasc Aging 2022;2:38. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/jca.2022.26

AMA Style

Wang X, Luo W, Chang J. Deficient Lmna in fibroblasts: an emerging role of non-cardiomyocytes in DCM. The Journal of Cardiovascular Aging. 2022; 2(3): 38. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/jca.2022.26

Chicago/Turabian Style

Wang, Xinjie, Weijia Luo, Jiang Chang. 2022. "Deficient Lmna in fibroblasts: an emerging role of non-cardiomyocytes in DCM" The Journal of Cardiovascular Aging. 2, no.3: 38. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/jca.2022.26

ACS Style

Wang, X.; Luo W.; Chang J. Deficient Lmna in fibroblasts: an emerging role of non-cardiomyocytes in DCM. J. Cardiovasc. Aging. 2022, 2, 38. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/jca.2022.26

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Cite This Article 6 clicks

Cite This Article 6 clicks

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at support@oaepublish.com.