Cellular aging and rejuvenation in ischemic heart disease: a translation from basic science to clinical therapy

Abstract

Ischemic heart disease and heart failure (HF) remain the leading causes of death worldwide. The inability of the adult heart to regenerate itself following ischemic injury and subsequent scar formation may explain the poor prognosis in these patients, especially when necrosis is extensive and leads to severe left ventricular dysfunction. Under physiological conditions, the crosstalk between cardiomyocytes and cardiac interstitial/vascular cells plays a pivotal role in cardiac processes by limiting ischemic damage or promoting repair processes, such as angiogenesis, regulation of cardiac metabolism, and the release of soluble paracrine or endocrine factors. Cardiovascular risk factors are the main cause of accelerated senescence of cardiomyocytes and cardiac stromal cells (CSCs), causing the loss of their cardioprotective and repairing functions. CSCs are supportive cells found in the heart. Among these, the pericytes/mural cells have the propensity to differentiate, under appropriate stimuli in vitro, into adipocytes, smooth muscle cells, osteoblasts, and chondroblasts, as well as other cell types. They contribute to normal cardiac function and have an antifibrotic effect after ischemia. Diabetes represents a condition of accelerated senescence. Among the new pharmacological armamentarium with hypoglycemic effect, gliflozins have been shown to reduce the incidence of HF and re-hospitalization, probably through the anti-remodeling and anti-senescent effect on the heart, regardless of diabetes. Therefore, either reducing the senescence of CSC or removing senescent cells from the infarcted heart could represent future antisenescence strategies capable of preventing the deterioration of heart function leading to HF.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Ischemic heart disease (IHD) and heart failure (HF), which often occur secondarily to atherosclerosis, are major causes of morbidity and mortality[1]. They can in part derive from the reduced ability of the adult heart to replace lost cardiomyocytes, occurring during and after a myocardial infarction and resulting in adverse cardiac remodeling, scar formation, and dysfunction manifesting as HF. This requires bypass surgery or angioplasty in approximately one million patients/year globally. Ischemic and non-ischemic HF, which is the inability of the heart to carry enough blood to meet the body’s energy demands, is currently classified according to the presence of reduced (HFrEF), preserved (HFpEF), or mid-range (HFmrEF) left ventricular ejection fraction. HFrEF and HFpEF differ in terms of demographics, etiology, pathophysiology, comorbidities, and response to therapy[2]. HFrEF is classically associated with male sex and coronary artery disease (CAD), while HFpEF is a more complex syndrome[3] characterized by several comorbidities such as arterial hypertension, atrial fibrillation, diabetes mellitus, obesity, and metabolic syndrome[2]. Besides differences in cardiovascular structure, risk factors, and co-morbidities, aging is a major risk factor and classically considered “not modifiable”, representing the common ground of all the different etiopathogenetic forms of HF.

Aging is often associated with changes in the immune system, manifesting as chronic low-grade inflammation[4,5]. We refer the reader to more specialized reviews from our research group for an in-depth discussion on immunity and cardiac disease[5]. However, most experimental studies do not consider aging as a variable when studying the molecular pathways in animal models of IHD. Likewise, the elderly are under-represented in clinical studies, which is certainly related to the fact that the acute phase of CAD generally develops in middle age. Hence, little is known about age-specific cellular mechanisms of cardiac disease and possible cell rejuvenation strategies as a tool for treating IHD.

In the following, we provide an overview of the emerging age-related cellular mechanisms contributing to IHD and provide an update on novel insights about cellular targets of aging in IHD. Emerging concepts to target cardiac aging are also covered.

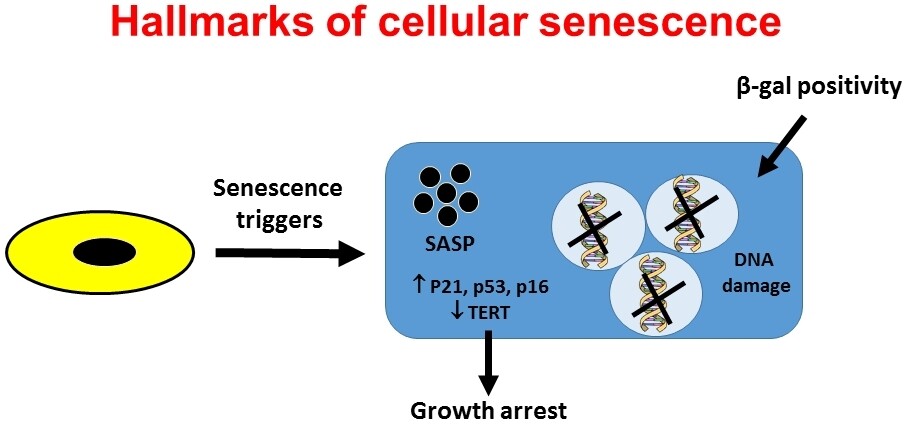

AGING AND SENESCENCE: THE DIFFERENCES

Aging can be defined as a physiological process that occurs over time, causing the cells to deteriorate. As aging causes organ deterioration and dysfunction, aging is a risk factor for various diseases, including cardiovascular disease, cancer, and dementia. Conversely, senescence is the process that recognizes aging cells and directs them to cell arrest, limiting the proliferation of aged or damaged cells[6]. Thus, senescence is necessary for tissue homeostasis and acts as a protective mechanism to destroy aging cells, which could otherwise lead to harmful outcomes such as cancer. The triggers of senescence are diverse and are not limited to aging, as it occurs in three different scenarios: senescence due to normal aging, senescence due to age-related diseases, and senescence due to therapy. The hallmarks of cellular senescence are growth arrest and the production of secreted factors, called SASP (senescence-associated secretory proteins)[7], which include several factors such as proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, and proteases [Figure 1]. Permanent cell growth arrest of senescent cells is enabled by specific alterations including chromatin remodeling, metabolic reprogramming, increased autophagy, decreased telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) activity and telomere shortening, and activation of p16INK4a/Rb and p53/p21CIP1 tumor suppressor networks[8]. Despite being a physiological mechanism of protection, senescence can contribute to organ dysfunction and aging-associated diseases. Under normal conditions, senescent cells are removed in the organs thanks to their clearance by the immune system, avoiding their accumulation. However, if there is immune system dysfunction (aging is one of the causes of immune compromise) or when tissue damage is excessive, the production of senescent cells exceeds the immune system’s ability to remove them. The accumulation of senescent cells leads to inflammation (so-called inflamaging), organ dysfunction, and aging-associated diseases.

Figure 1. The hallmarks of cellular senescence. Cellular senescence can be defined as the irreversible growth arrest that occurs when the cells encounter a stressor. Senescent cells differ from other nondividing (quiescent, terminally differentiated) cells in several ways, although no single feature of the senescent phenotype is exclusively specific. The hallmarks of senescent cells include an essentially irreversible growth arrest; expression of senescence associated (SA)-β gal activity and p16INK4a; robust secretion of numerous growth factors, cytokines, proteases, and other proteins (SASP); and nuclear foci containing damaged DNA. SASP: Senescence associated secretory proteins; TERT: telomerase reverse transcriptase.

AGING, SENESCENCE AND CELLULAR TARGETS IN ISCHEMIC AND NON-ISCHEMIC HEART DISEASE

Aging alters the cytoarchitecture of cardiomyocytes by increasing their size, altering interorganellar communication, and causing mitochondrial fragmentation and many other phenotipic changes [Table 1][9]. In IHD, aging leads to the loss of cardiomyocytes and the progressive development of IHD, in part due to impaired coupling of cardiomyocytes with blood vessels, due to impaired angiogenesis, which is normally orchestrated by cardiac stromal cells (CSCs). CSCs are supportive cells found in the heart, including fibroblasts, progenitor cells, pericytes, and fibrocytes[10]. They are characterized by residual multipotency toward mesenchymal lineages[11]. Among these, pericytes/mural cells have the propensity to differentiate, under appropriate stimuli in vitro, into adipocytes, smooth muscle cells, osteoblasts, and chondroblasts, as well as other cell types; they contribute to normal cardiac function and play an antifibrotic effect after ischemia. While collateral vessel formation, as alternative routes for blood supply, occurs in younger patients, in the elderly many collateral vessels do not form vascular networks adequate to compensate for the loss of the original blood supply. These deranged mechanisms may play a key role in altering transcriptional regulatory networks, which trigger delayed recovery (stunning) and persistent hypoperfusion (hibernation) and promote the transition from ischemia to necrosis and, later, to HF. In addition, this interplay orchestrates the adaptive changes occurring in the myocardium not directly affected by ischemia, which may undergo adaptive processes, such as hypertrophy, fibrosis, and dilatation, eventually resulting in chronic HF[12].

Phenotype of the aged cardiac cells

| Main cellular and molecular changes | Ref. |

| ↑ Cell size | [45] |

| ↑ Number of nuclei | [45] |

| ↓ Cell number | [45] |

| ↓ Number of mithocondria | [46] |

| ↑ Mithocondria fragmentation | [46] |

| ↓ Telomere lenght | [47] |

| ↓ TERT activity | [47] |

| ↑ DNA damage | [47] |

| ↑ Chromatin modification | [47] |

| ↑ Cell cycle arrest | [47] |

| ↑ p53 | [48] |

| ↑ p16/INK4A | [48] |

| ↑ ROS | [49] |

| ↓ HSP70 | [49] |

| ↓ Hemeoxygenase-1 | [49] |

| ↓ Mitochondrial respiratory chain | [46] |

| ↓ CM contractility | [50] |

| ↓ CM relaxation | [50] |

| ↓ Connexin 43 | [51] |

| ↑ Connexin 43 lateralization | [51] |

| ↓ FA oxidation | [52] |

| ↑ Secretion of SASP | [53] |

| ↓ Autophagy | [54] |

Interstitial/vascular cells are involved in this degenerative process. Under physiological conditions, the crosstalk between cardiomyocytes and interstitial/vascular cells, providing the scaffold for blood supply, plays a pivotal role in a variety of cardiac processes (such as the regulation of cardiac metabolism, the release of soluble paracrine or endocrine factors with pro-angiogenic activity, and the secretion of IL-6 which plays an important role during cardiac development and postnatally for cardiomyocyte growth and survival). Thus, the CSC secretome is able to ultimately control angiogenesis, support the growth and survival of cardiomyocyte, and provide cardioprotection[13,14]. These processes require the presence of a supportive “niche”, consisting of CSC, epicardium-derived soluble factors[15], and a defined extracellular matrix[16]. CSC can be isolated from ventricle and auricle tissues. In culture, they adhere to the plastic and migrate from tissue explants. On the basis of distinct cell surface markers, including alkaline phosphatase (Alpl), stem cells antigen-1 (Sca1), platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta (PDGFRbeta), and neuron-glial antigen 2 (NG2), various CSC have been isolated and tested for their paracrine effects to restore cardiac function after ischemic injury[17]. These include, among others, pericytes (mural cells) expressing Alpl, PDGFRbeta, and NG2[18] and the embryonic muscle pericyte (mesoangioblasts) that, when injected into the ventricle after coronary artery ligation, resulted in a 50% recovery of cardiac function[19]. CSCs also include cells expressing mesenchymal surface markers (CD90, CD105, and CD73) and negative for hematopoietic markers (CD34, CD11b, CD45, CD19, and HLA-DR), highlighting the complexity in the composition of the cardiac stromal niche[20]. Thus, CSCs appear to contribute to cardiac healing after ischemic injury and lead to improved heart function when tested in animal models of post-ischemic HF. They can undergo adipogenic differentiation in the heart in some pathological conditions such as obesity[21] and arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (ACM)[22,23]. In particular, in ACM, the mesenchymal component of CSCs is believed to be the source of cardiac adipocytes[22,23]. Human-derived CSCs have recently been shown to express the ACE2 receptor and are susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection[24]. As a result, CSCs act as reservoirs for viral particles replication and trigger an intense proinflammatory and profibrotic response. CSCs therefore participate in heart damage from SARS-CoV-2 through a double mechanism, direct replication of the virus and the production of proinflammatory cytokine storms in heart tissue[24]. Whatever the mechanism leading to cardiac repair and the improvement of heart function, aging negatively impacts on the healing potential of cardiac cells, including CSCs[25]. Cardiovascular risk factors are the major cause of accelerated senescence of cardiomyocytes and CSCs, causing loss of their cardioprotective and repairing functions, which can ultimately lead to HF. With cellular aging, favored by exposure to cardiovascular risk factors, comorbidities and various stressors, such as bouts of ischemia and/or ischemia-reperfusion, the function and crosstalk of CSCs and parenchymal cells are diminished, hampering their cardioprotective potential. Diabetes, mostly occurring on the background of the so-called metabolic syndrome, is one of the most relevant of such comorbidities, since it can lead to left ventricular dysfunction even in the absence of IHD. In addition, its presence worsens the prognosis after an ischemic event, doubling mortality after an acute MI[1]. Diabetes causes accelerated senescence in systemic tissues and organs, including vessels and the heart. Diabetes-induced cellular and molecular changes are largely comparable to those induced by aging, with some specific expressional signatures not only playing an innocent bystander role but also causally linked to diabetes-induced cellular senescence [Table 2][26,27].

HOW TO REJUVENATE THE AGING HEART

Although there is an increased incidence of HF in older age groups worldwide, the elderly are rarely randomized in clinical trials[12]. This implies that there is no scientific evidence to justify the efficacy or toxicity of the therapies applied in older patients. There is a limited number of human studies that have assessed whether age reduces the efficacy of ongoing anti-ischemic therapies and the evolution towards HF. A retrospective analysis has shown how remote ischemic conditioning exerts cardioprotection in ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients regardless of age[28]. In contrast, a phase III study demonstrated neutral effects of remote ischemic conditioning in STEMI patients regardless of age[28]. Among the treatments capable of modifying the natural history of HF, inhibitors of the sodium-glucose transporter type 2 (SGLT2) (gliflozins)[29,30] reduce the incidence of HF in patients with HFrEF and HFpEF, regardless of the presence of diabetes. However, data on the effects of gliflozins in older age groups are limited. A sub-analysis of the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial examined the effects of dapagliflozin in diabetic patients within age subgroups[31]. The study demonstrated the persistence of beneficial cardiovascular and renal effects of dapagliflozin in a robust number of elderly and very elderly participants. A randomized, double-blind study demonstrated the efficacy of dapagliflozin on various endpoints (reduction in blood glucose, body weight, and blood pressure) in all patient groups regardless of age. The main limitation of this study is the limited randomization of elderly patients[32].

However, cellular and molecular mechanisms that confer protection from developing HF with these pharmacological interventions are largely unknown. Consistent with the demonstration of the persistence of beneficial effects even in older patients from the few clinical trials carried out, one hypothesis is that gliflozins[33] exert anti-senescence effects in the cardiovascular system. Our research group recently demonstrated that empagliflozin improved cardiac dysfunction and reduced cardiac fibrosis and cellular senescence in a mouse model of streptozotocin-induced type 1 diabetes (STZ)[33]. At the cellular level, we found that empagliflozin exerts antisenescence effects on CSCs[33]. Mechanisms by which empagliflozin reduces CSC senescence are likely multiple. First, we showed that empagliflozin restored PI3K/Akt downregulation in cultured CSCs exposed to high glucose, suggesting a pro‐survival effect of this drug[33]. Secondly, one of the relevant components of CSCs, the cardiac fibroblasts, is known to express sodium‐hydrogen exchanger 1 (NHE‐1)[34], which is an established molecular target of SGLT2 inhibitors. This suggest that empagliflozin may reduce senescence in CSCs exposed to high glucose through off-target effects of SGLT2[33]. These effects may explain the unexpected benefits of empagliflozin on cardiac function in older diabetic patients. Diabetic patients thus appear to potentially benefit from therapies that would revert senescence of myocardial and vascular cells, an approach referred to as “anti-senescence” or “rejuvenating” therapies[35,36]. Our research group demonstrated the ability to rejuvenate mesenchymal stromal cells isolated from adipose tissue of old mice through the overexpression of two genes, telomerase and myocardin[14,36-38], the first coding for the catalytic subunit of telomerase (i.e., TERT), which has anti-senescence properties, the other encoding for myocardin, a nuclear transcription cofactor for myogenic genes. This new approach would allow reconstituting aged adipose tissue by rejuvenating existing cells or by injecting their angiogenic cell products into ischemic tissue[39]. An alternative approach is to eliminate senescent cells through “senolytic” therapies[40,41]. Table 3 summarizes the main senotherapeutics in aging-associated cardiovascular diseases. We refer the reader to more specialized reviews of our research group for an in-depth discussion on senotherapy and cardiac diseases[42]. Either reducing CSC senescence or removing senescent cells from the infarcted heart could represent future antisenescence strategies capable of preventing the deterioration of heart function occurring in a diabetic animal model, leading to HF.

Senotherapeutics in aging-associated cardiac diseases

| Senolitic compound | Effects | Ref. |

| Desatinib | ↑ Vamotricity, ↓ vascular calcification | [62] |

| Quercitin | ↑ Vamotricity, ↓ vascular calcification | [63] |

| Navitoclax | ↓ Adverse myocardial remodeling | [64] |

| Cardiac glycosides | ↑ Cardiac function | [65] |

| HSP90 chaperone inhibitors | ↓ Atherosclerosis | [66] |

| Resveratrol | ↓ Endothelial inflammation, ↓ arterial stiffening | [67] |

| SIRT1 specific activator | ↓ Arterial hypertension, ↓ arterial stiffening | [68] |

| Caloric restriction | ↓ Abdominal aortic aneurysm | [69] |

| Pioglitazone | ↑ TERT activity in endothelial cells | [70] |

| Rapamycin | ↓ Atherosclerosis | [71] |

| Statins | ↓ SASP | [72] |

| Polyphenols | ↓ ROS | [67] |

CONCLUSIONS

Cardiac aging has been shown to be associated with a higher incidence of IHD and a decrease in the efficiency of anti-ischemic treatments. From a cellular point of view, the reasons linking cardiac aging with cardiac dysfunction include cellular senescence of cardiomyocytes and the non-cardiomyocyte cell population of the heart. Why older people have worse outcomes than younger patients is still unclear, and targeted studies on animal models that take into account the comorbidities of found in the elderly would allow understanding how aging impacts cardiac disease[43]. Future research could rely on an unbiased approach based on metabolomics and proteomics data capable of identifying the signaling networks activated by aging in the ischemic heart[44]. The integration of different “omics” such as epigenomic, proteomic, metabolomic, and transcriptomic analyses would allow identifying new therapeutic targets for aging-associated IHD.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributionsThe author contributed solely to the article.

Availability of data and materialsNot applicable.

Financial support and sponsorshipThis work was supported by a grant from Incyte to Rosalinda Madonna and funds from Ministero dell’Istruzione, Università e Ricerca Scientifica to Rosalinda Madonna (549901_2020_Madonna:Ateneo). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, the decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interestThe author declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participateNot applicable.

Consent for publicationNot applicable.

Copyright© The Author(s) 2022.

REFERENCES

1. Timmis A, Townsend N, Gale C, et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. European society of cardiology: cardiovascular disease statistics 2017. Eur Heart J 2018;39:508-79.

2. McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2021;42:3599-726.

3. Argulian E, Chandrashekhar Y, Shah SJ, et al. Teasing apart heart failure with preserved ejection fraction phenotypes with echocardiographic imaging: potential approach to research and clinical practice. Circ Res 2018;122:23-5.

5. Steffens S, Nahrendorf M, Madonna R. Immune cells in cardiac homeostasis and disease: emerging insights from novel technologies. Eur Heart J ;2021:ehab842.

6. Muñoz-Espín D, Serrano M. Cellular senescence: from physiology to pathology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2014;15:482-96.

7. Kuilman T, Peeper DS. Senescence-messaging secretome: SMS-ing cellular stress. Nat Rev Cancer 2009;9:81-94.

8. Kuilman T, Michaloglou C, Mooi WJ, Peeper DS. The essence of senescence. Genes Dev 2010;24:2463-79.

9. Ruiz-Meana M, Bou-Teen D, Ferdinandy P, et al. Cardiomyocyte ageing and cardioprotection: consensus document from the ESC working groups cell biology of the heart and myocardial function. Cardiovasc Res 2020;116:1835-49.

10. Souders CA, Bowers SL, Baudino TA. Cardiac fibroblast: the renaissance cell. Circ Res 2009;105:1164-76.

11. Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, et al. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science 1999;284:143-7.

13. Reus TL, Robert AW, Da Costa MB, de Aguiar AM, Stimamiglio MA. Secretome from resident cardiac stromal cells stimulates proliferation, cardiomyogenesis and angiogenesis of progenitor cells. Int J Cardiol 2016;221:396-403.

14. Madonna R, Guarnieri S, Kovácsházi C, et al. Telomerase/myocardin expressing mesenchymal cells induce survival and cardiovascular markers in cardiac stromal cells undergoing ischaemia/reperfusion. J Cell Mol Med 2021;25:5381-90.

15. Limana F, Capogrossi MC, Germani A. The epicardium in cardiac repair: from the stem cell view. Pharmacol Ther 2011;129:82-96.

16. Forbes SJ, Rosenthal N. Preparing the ground for tissue regeneration: from mechanism to therapy. Nat Med 2014;20:857-69.

17. Mayourian J, Ceholski DK, Gonzalez DM, et al. Physiologic, pathologic, and therapeutic paracrine modulation of cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Circ Res 2018;122:167-83.

18. Eschenhagen T, Bolli R, Braun T, et al. Cardiomyocyte regeneration: a consensus statement. Circulation 2017;136:680-6.

19. Galli D, Innocenzi A, Staszewsky L, et al. Mesoangioblasts, vessel-associated multipotent stem cells, repair the infarcted heart by multiple cellular mechanisms: a comparison with bone marrow progenitors, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2005;25:692-7.

20. Traktuev DO, Merfeld-Clauss S, Li J, et al. A population of multipotent CD34-positive adipose stromal cells share pericyte and mesenchymal surface markers, reside in a periendothelial location, and stabilize endothelial networks. Circ Res 2008;102:77-85.

22. Sommariva E, Brambilla S, Carbucicchio C, et al. Cardiac mesenchymal stromal cells are a source of adipocytes in arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J 2016;37:1835-46.

23. Stadiotti I, Piacentini L, Vavassori C, et al. Human cardiac mesenchymal stromal cells from right and left ventricles display differences in number, function, and transcriptomic profile. Front Physiol 2020;11:604.

24. Amendola A, Garoffolo G, Songia P, et al. Human cardiosphere-derived stromal cells exposed to SARS-CoV-2 evolve into hyper-inflammatory/pro-fibrotic phenotype and produce infective viral particles depending on the levels of ACE2 receptor expression. Cardiovasc Res 2021;117:1557-66.

25. Rotini A, Martínez-Sarrà E, Duelen R, et al. Aging affects the in vivo regenerative potential of human mesoangioblasts. Aging Cell 2018;17:e12714.

26. Perkisas S, Vandewoude M. Where frailty meets diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2016;32 Suppl 1:261-7.

27. Palmer AK, Tchkonia T, LeBrasseur NK, Chini EN, Xu M, Kirkland JL. Cellular senescence in type 2 diabetes: a therapeutic opportunity. Diabetes 2015;64:2289-98.

28. Sloth AD, Schmidt MR, Munk K, et al. CONDI Investigators. Impact of cardiovascular risk factors and medication use on the efficacy of remote ischaemic conditioning: post hoc subgroup analysis of a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2015;5:e006923.

29. Persson F, Nyström T, Jørgensen ME, et al. Dapagliflozin is associated with lower risk of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in people with type 2 diabetes (CVD-REAL Nordic) when compared with dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor therapy: a multinational observational study. Diabetes Obes Metab 2018;20:344-51.

30. Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, et al. EMPA-REG OUTCOME Investigators. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2117-28.

31. Cahn A, Mosenzon O, Wiviott SD, et al. Efficacy and safety of dapagliflozin in the elderly: analysis from the DECLARE-TIMI 58 study. Diabetes Care 2020;43:468-75.

32. Leiter LA, Cefalu WT, de Bruin TW, Gause-Nilsson I, Sugg J, Parikh SJ. Dapagliflozin added to usual care in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus with preexisting cardiovascular disease: a 24-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with a 28-week extension. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;62:1252-62.

33. Madonna R, Doria V, Minnucci I, Pucci A, Pierdomenico DS, De Caterina R. Empagliflozin reduces the senescence of cardiac stromal cells and improves cardiac function in a murine model of diabetes. J Cell Mol Med 2020;24:12331-40.

34. Maly K, Strese K, Kampfer S, et al. Critical role of protein kinase C α and calcium in growth factor induced activation of the Na+/H+ exchanger NHE1. FEBS Letters 2002;521:205-10.

35. Katare R, Caporali A, Zentilin L, et al. Intravenous gene therapy with PIM-1 via a cardiotropic viral vector halts the progression of diabetic cardiomyopathy through promotion of prosurvival signaling. Circ Res 2011;108:1238-51.

36. Madonna R, Pieragostino D, Rossi C, et al. Transplantation of telomerase/myocardin-co-expressing mesenchymal cells in the mouse promotes myocardial revascularization and tissue repair. Vascul Pharmacol 2020;135:106807.

37. Madonna R, Taylor DA, Geng YJ, et al. Transplantation of mesenchymal cells rejuvenated by the overexpression of telomerase and myocardin promotes revascularization and tissue repair in a murine model of hindlimb ischemia. Circ Res 2013;113:902-14.

38. Madonna R, Willerson JT, Geng YJ. Myocardin a enhances telomerase activities in adipose tissue mesenchymal cells and embryonic stem cells undergoing cardiovascular myogenic differentiation. Stem Cells 2008;26:202-11.

40. Baker DJ, Childs BG, Durik M, et al. Naturally occurring p16(Ink4a)-positive cells shorten healthy lifespan. Nature 2016;530:184-9.

41. Childs BG, Baker DJ, Wijshake T, Conover CA, Campisi J, van Deursen JM. Senescent intimal foam cells are deleterious at all stages of atherosclerosis. Science 2016;354:472-7.

42. Balistreri CR, Madonna R, Ferdinandy P. Is it the time of seno-therapeutics application in cardiovascular pathological conditions related to ageing? Curr Res Pharmacol Drug Discov 2021;2:100027.

43. Gale CP, Cattle BA, Woolston A, et al. Resolving inequalities in care? Eur Heart J 2012;33:630-9.

44. Perrino C, Barabási AL, Condorelli G, et al. Epigenomic and transcriptomic approaches in the post-genomic era: path to novel targets for diagnosis and therapy of the ischaemic heart? Cardiovasc Res 2017;113:725-36.

45. Hacker TA, McKiernan SH, Douglas PS, Wanagat J, Aiken JM. Age-related changes in cardiac structure and function in Fischer 344 x Brown Norway hybrid rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2006;290:H304-11.

46. Lesnefsky EJ, Chen Q, Hoppel CL. Mitochondrial metabolism in aging heart. Circ Res 2016;118:1593-611.

47. Madonna R, De Caterina R, Willerson JT, Geng YJ. Biologic function and clinical potential of telomerase and associated proteins in cardiovascular tissue repair and regeneration. Eur Heart J 2011;32:1190-6.

48. Cai Y, Liu H, Song E, et al. Deficiency of telomere-associated repressor activator protein 1 precipitates cardiac aging in mice via p53/PPARα signaling. Theranostics 2021;11:4710-27.

49. Liochev SI. Reactive oxygen species and the free radical theory of aging. Free Radic Biol Med 2013;60:1-4.

50. Häseli S, Deubel S, Jung T, Grune T, Ott C. Cardiomyocyte contractility and autophagy in a premature senescence model of cardiac aging. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2020;2020:8141307.

51. Moscato S, Cabiati M, Bianchi F, et al. Heart and liver connexin expression related to the first stage of aging: a study on naturally aged animals. Acta Histochem 2020;122:151651.

52. Ma Y, Li J. . Metabolic shifts during aging and pathology. In: Terjung R, editor. Comprehensive Physiology. Wiley; 2011. p. 667-86.

53. Coppé JP, Patil CK, Rodier F, et al. Senescence-associated secretory phenotypes reveal cell-nonautonomous functions of oncogenic RAS and the p53 tumor suppressor. PLoS Biol 2008;6:2853-68.

54. Ren J, Sowers JR, Zhang Y. Metabolic stress, autophagy, and cardiovascular aging: from pathophysiology to therapeutics. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2018;29:699-711.

55. Mouton RE, Venable ME. Ceramide induces expression of the senescence histochemical marker, β-galactosidase, in human fibroblasts. Mech Ageing Dev 2000;113:169-81.

56. Tran D, Bergholz J, Zhang H, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-1 regulates the SIRT1-p53 pathway in cellular senescence. Aging Cell 2014;13:669-78.

57. Kim KS, Seu YB, Baek SH, et al. Induction of cellular senescence by insulin-like growth factor binding protein-5 through a p53-dependent mechanism. Mol Biol Cell 2007;18:4543-52.

58. Davalos AR, Kawahara M, Malhotra GK, et al. p53-dependent release of Alarmin HMGB1 is a central mediator of senescent phenotypes. J Cell Biol 2013;201:613-29.

59. Kim CS, Park HS, Kawada T, et al. Circulating levels of MCP-1 and IL-8 are elevated in human obese subjects and associated with obesity-related parameters. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006;30:1347-55.

60. Elzi DJ, Lai Y, Song M, Hakala K, Weintraub ST, Shiio Y. Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1--insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 cascade regulates stress-induced senescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:12052-7.

61. Shakeri H, Lemmens K, Gevaert AB, De Meyer GRY, Segers VFM. Cellular senescence links aging and diabetes in cardiovascular disease. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2018;315:H448-62.

62. Zhu Y, Tchkonia T, Pirtskhalava T, et al. The Achilles' heel of senescent cells: from transcriptome to senolytic drugs. Aging Cell 2015;14:644-58.

63. Roos CM, Zhang B, Palmer AK, et al. Chronic senolytic treatment alleviates established vasomotor dysfunction in aged or atherosclerotic mice. Aging Cell 2016;15:973-7.

64. Walaszczyk A, Dookun E, Redgrave R, et al. Pharmacological clearance of senescent cells improves survival and recovery in aged mice following acute myocardial infarction. Aging Cell 2019;18:e12945.

65. Guerrero A, Herranz N, Sun B, et al. Cardiac glycosides are broad-spectrum senolytics. Nat Metab 2019;1:1074-88.

66. Lazaro I, Oguiza A, Recio C, et al. Targeting HSP90 ameliorates nephropathy and atherosclerosis through suppression of NF-κB and STAT signaling pathways in diabetic mice. Diabetes 2015;64:3600-13.

67. Mattison JA, Wang M, Bernier M, et al. Resveratrol prevents high fat/sucrose diet-induced central arterial wall inflammation and stiffening in nonhuman primates. Cell Metab 2014;20:183-90.

68. Gao D, Zuo Z, Tian J, et al. Activation of SIRT1 attenuates klotho deficiency-induced arterial stiffness and hypertension by enhancing AMP-activated protein kinase activity. Hypertension 2016;68:1191-9.

69. Liu Y, Wang TT, Zhang R, et al. Calorie restriction protects against experimental abdominal aortic aneurysms in mice. J Exp Med 2016;213:2473-88.

70. Werner C, Gensch C, Pöss J, Haendeler J, Böhm M, Laufs U. Pioglitazone activates aortic telomerase and prevents stress-induced endothelial apoptosis. Atherosclerosis 2011;216:23-34.

71. Walters HE, Deneka-Hannemann S, Cox LS. Reversal of phenotypes of cellular senescence by pan-mTOR inhibition. Aging (Albany NY) 2016;8:231-44.

Cite This Article

Export citation file: BibTeX | RIS

OAE Style

Madonna R. Cellular aging and rejuvenation in ischemic heart disease: a translation from basic science to clinical therapy. J Cardiovasc Aging 2022;2:12. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/jca.2021.34

AMA Style

Madonna R. Cellular aging and rejuvenation in ischemic heart disease: a translation from basic science to clinical therapy. The Journal of Cardiovascular Aging. 2022; 2(1): 12. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/jca.2021.34

Chicago/Turabian Style

Madonna, Rosalinda. 2022. "Cellular aging and rejuvenation in ischemic heart disease: a translation from basic science to clinical therapy" The Journal of Cardiovascular Aging. 2, no.1: 12. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/jca.2021.34

ACS Style

Madonna, R. Cellular aging and rejuvenation in ischemic heart disease: a translation from basic science to clinical therapy. J. Cardiovasc. Aging. 2022, 2, 12. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/jca.2021.34

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Cite This Article 11 clicks

Cite This Article 11 clicks

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at support@oaepublish.com.